The workshop with two suns

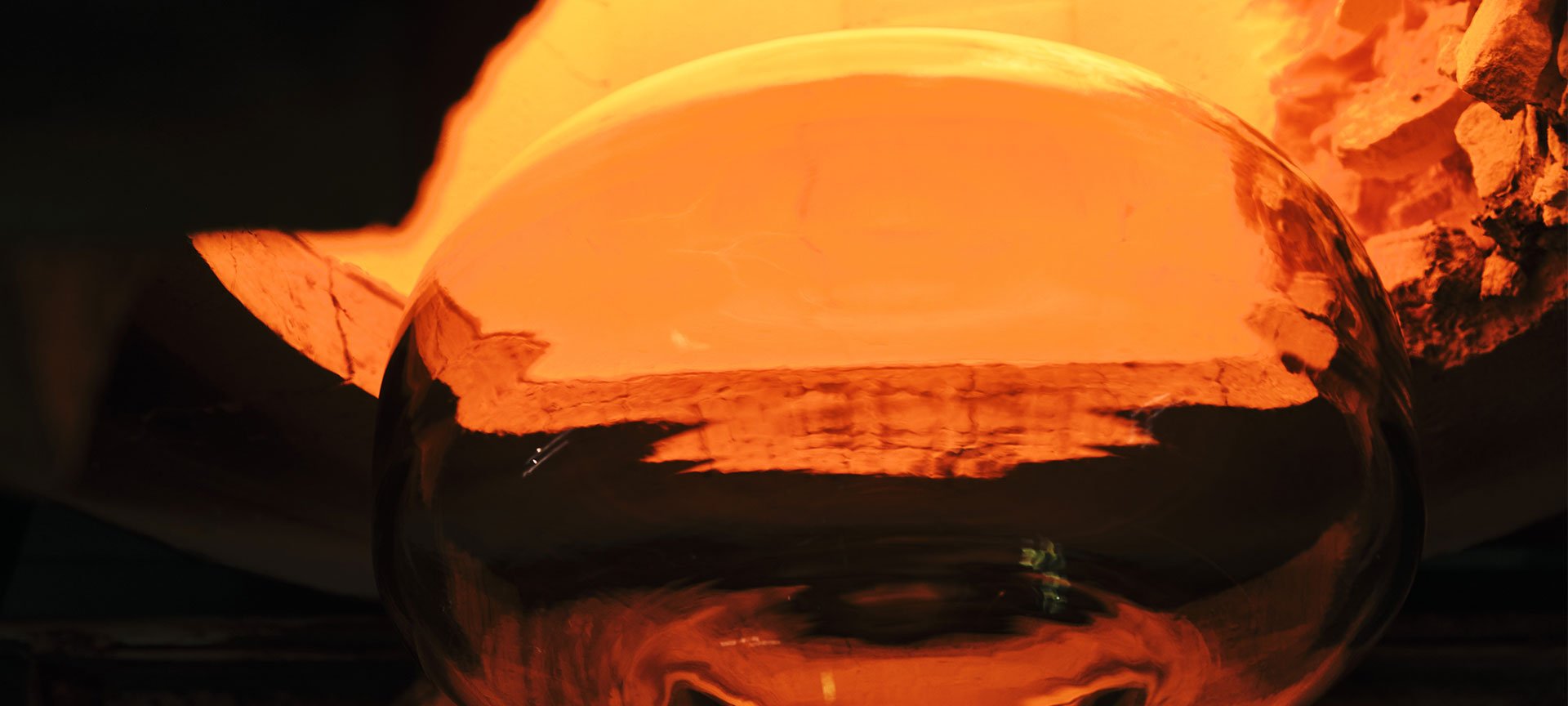

In the hot workshop, two sun furnaces continually feed blowers with crystal. The molten crystal reaches 1450 degrees Celsius, more than a quarter of the temperature of the Sun's surface. In Moselle, during winter, the crystal workshop is as hot as a Mediterranean summer. The crystal makers are bare-armed.

“It's a body experience. We are strangely augmented, like totally immersed in the light on a summer day. The light illuminates the parts of our body and lowers our voice. The Sun makes us strangely silent,” is how French philosopher Emma Carenini describes it. The philosopher takes a closer look at the heliotropic thinkers who took their cue from the Sun's bodily effects. Among them, Nietzsche, and Camus in his La pensée de midi (generally translated as Thought at the meridian) were inspired by the Mediterranean sunlight. She explores our lives through the prism of this prodigal energy, considered a common good since ancient times, and still untamed by humans even when the question of energy resources arises today.

“I was 23 when I first entered the Saint-Louis manufacture,” furnace conductor Christophe Enaux reveals. “It started as a temp job. But I was magnetized by the light and warmth of the crystal.” Since then, the craftsman has spent over two decades watching over the fueling of the fire and the fusion of the crystal. He shares how a careful observation has become a meditation. In his eyes, the fascinating bursts of magma, the ever-changing glow, are just like a fire or the reflections of the Sun on the sea.

The quiet hours at nights and during weekends spent watching over the crystal in the workshop, regain their stellar malleability. Just as an ancient sundial was not indicating time, but the relative position of a human being to the planets. But we have lost this quotidian and reassuring anchor point of the solar system in the vast and mobile universe, by changing our solar calendars. Instead of reading the clock, crystal makers seize the best timing according to heat. They read the temperature by the color of the molten crystal, which sets the rhythm of their movements.

“The more incandescent the light, the hotter the material. It is just like the Sun at its zenith. Conversely, reds show its cooling, like the Sun approaching dusk,” Tristan Ladaique, the head of production explains. “This intimate understanding of crystal is unfathomable to the layman,” the engineer continues. “It requires years of observation and patience to perfect.”

This tacit dialogue between man and material often tells the crystal makers if the material is alive by its throbs, belches, or fades. After the runny material is ‘scooped’ from the furnace and dazzling like a little sun at the end of a metal pipe, the master crystal makers blow and sculpt it. It flows from one tool to another like stellar honey, as if dozens of fireballs are orbiting around the furnaces. A satellite waltz that cannot be translated to passers-by. And yet, the creative energy of fusion acts impartial on everyone. Like the Sun, fusion is a source of metamorphosis and creative life. For centuries, the power of this material has attracted crystal makers and travelers to dream the impossible, to make pilgrimages from afar, sometimes from the other side of the Earth, just to get close to the Sun.

Vosges,creation inspired by the spirit of the forest

DISCOVER MORE